Treatment of drug-resistant TB in South Africa has been transformed over the past decade.

Most people with the illness no longer have to have daily injections, and treatment is often completed in nine months, compared with 18 to 24 months in the past.

Perhaps most important is that fewer people are dying of drug-resistant TB, and there is less hearing loss, a common side effect of the injections used in the past.

Key to this transformation in our public sector has been the roll-out of the antibiotics, bedaquiline and linezolid.

These two drugs, plus another two, in some cases even four or five, make up drug-resistant TB treatment today.

Broadly speaking, the more resistant someone’s TB has become, the more complicated the treatment combination and the longer the treatment lasts. But that may be about to change, with a new three-drug regimen taken for just six months.

One patient, Nelisiwe Ngcobo, knows first-hand how exhausting the old drug-resistant TB regimens can be.

“It was a terrible time for me because I had to take TB tablets for long [over and above] my other chronic medication. In a day, I took between 28 and 30 tablets. I was crying all the time because the medication I had to take was just too much. I lost weight and I was frustrated. It was a painful process and, because of the injections, I had all sorts of bumps on the lower back. I hated every moment of taking my injection.”

Ngcobo was a participant in a briefing on the announcement of a new clinical access programme (CAP) hosted in December by the TB Alliance, a non-profit drug developer responsible for the development of the drug, pretomanid.

The BPaL access programme

In an effort to help patients such as Ngcobo, the Wits Health Consortium and the national department of health are starting an initiative to provide a new, shorter treatment regimen for people affected with extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB).

The programme was meant to start in KwaZulu-Natal, but will now start in Gauteng either this month or early in February.

It will enrol 400 people with XDR-TB for treatment with a six-month, all-oral regimen of three drugs – bedaquiline, pretomanid and linezolid (known as the BPaL regimen).

Pretomanid is not yet registered in South Africa and its doses are donated to the programme by the pharmaceutical company Mylan, one of TB Alliance’s global commercialisation partners for the drug.

The programme is funded by the US Agency for International Development (USAid).

Since pretomanid has not yet been registered by the SA Health Products Regulatory Authority, permission from the regulator was required to provide the drug as part of a CAP – a means to make an unregistered medicine available to people under controlled conditions, thus allowing for both access to the drug for strict monitoring of potential side effects, and for data on safety and efficacy to be gathered.

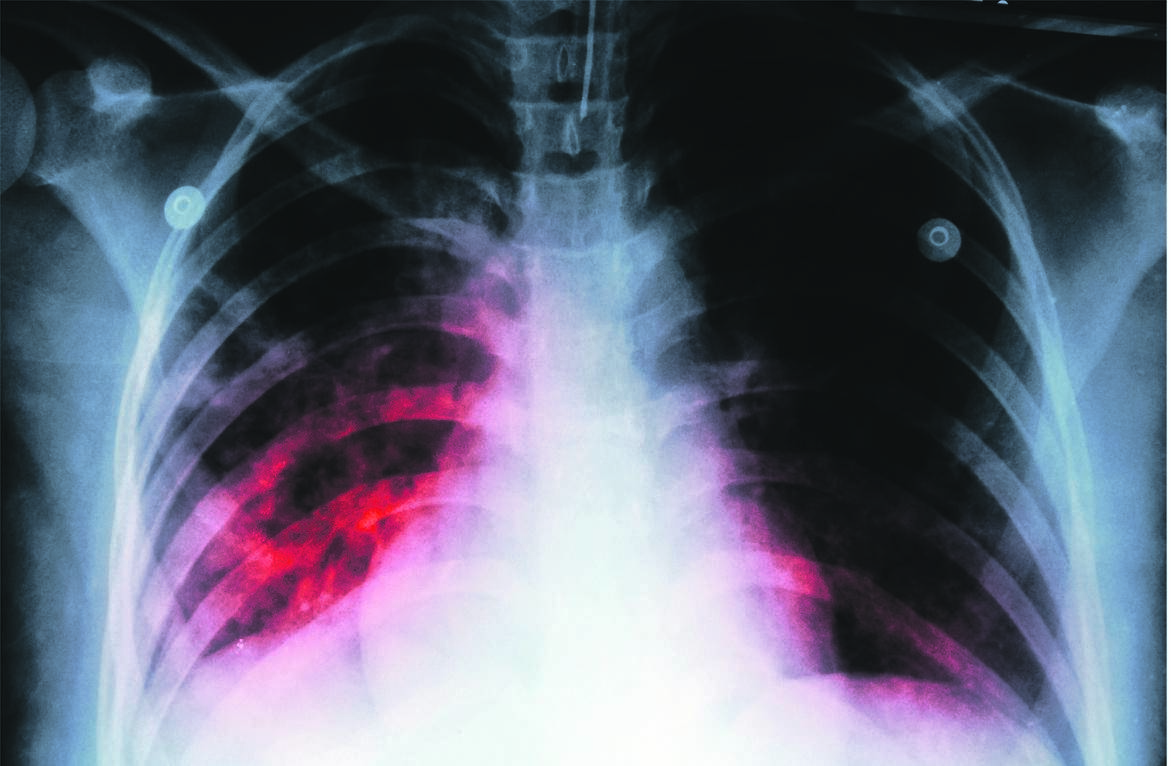

Read: X-rays and AI could transform TB detection in SA, but red tape might delay things

The US Food and Drug Administration registered pretomanid in August 2019, but only for use as part of the BPaL regimen.

The drug was added to the World Health Organisation’s (WHO’s) list of prequalified medicines in November 2020.

Who is eligible?

Coordinated by the Wits Health Consortium, the BPaL CAP will enrol participants aged 14 and older with confirmed sputum pulmonary XDR-TB, fluoroquinolone-resistant drug-resistant TB and selected rifampicin-resistant TB cases that have been pre-approved for treatment by the department of health (rifampicin is one of the four drugs used to treat drug-sensitive TB).

The programme will start by enrolling patients from high-burden provinces including the Western Cape, Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal and North West.

‘A huge improvement’

Speaking on a webinar announcing the programme in December, Dr Francesca Conradie of Wits University said: “TB is the world’s deadliest infectious disease. When I was an intern many years ago, 52 out of 53 people who acquired the disease [drug-resistant TB] died. With this access programme, 400 patients will have access to treatment for the first time outside the clinical trial. It is a shorter treatment and only 23 tablets per week. This is a huge improvement,” she said.

The BPaL regimen resulted in a favourable outcome in 90% of patients with XDR-TB or pre-XDR-TB in a landmark study conducted in South Africa, called Nix-TB.

In an interview with Spotlight, Conradie explained that the Nix-TB trial had 109 participants.

“This was not a randomised trial, so there was no control or comparison group. Many of the patients who were started in the beginning were very ill and had been for years. Even in the first 10 patients, we were able to see what I thought were remarkable recoveries. Patients put on weight and stopped coughing and sweating at night. Soon, we were not able to detect TB in their sputum anymore and 90% of the patients were cured.”

Ngcobo, who was one of the patients in the initial clinical trial, said when she was told about the trial she jumped at the opportunity to participate.

“I wanted to be part of the change. I wanted my name to be counted [among] the names of people who made this work. Lo and behold, it was only a few tablets. It was practical.”

Ncgobo said she was concerned at first that there were only a small number of patients participating in the trial, whereas there were many who suffered like her.

“I continued with the programme and I’m happy to report that I’m clear and have remained clear since February 2020.”

Conradie explains that in the CAP they will monitor people taking the BPaL regimen for safety and efficacy.

“We look to see if the medications cause any harm by doing regular blood tests and clinical assessments, including eye tests and nerve examinations. While patients are on treatment, we see them every two weeks in the beginning and then once a month after the second month. To assess if someone is cured from TB (efficacy) we send a specimen of their sputum to the laboratory every month.

“This is cultured to see if there are any live TB bacilli remaining. We declare someone cured if they do not have TB in their sputum for at least three months and then we follow up with them for a year to make sure it does not come back.”

Read: Getting Gauteng’s HIV and TB response back on track

She also tells Spotlight that they are planning to expand these indications to patients with drug-resistant TB, which is about 14 000 patients per year.

As part of the project, USAid has donated 34 electrocardiograph (ECG) machines.

These are important to have in the healthcare system since some drugs used to treat drug-resistant TB, including some in the BPaL regimen, can cause cardiac abnormalities – something that can be picked up early with regular ECGs.

Questions remain about the BPaL regimen

Lindsay McKenna, TB Project co-director at the US-based NGO Treatment Action Group, tells Spotlight that South Africa has always been at the forefront, an early adopter and a leader when it comes to TB.

“South Africa was ahead of the WHO in terms of offering bedaquiline in place of the injectable agents. Data and experience from this country shaped [global] policy for all-oral bedaquiline-based regimens as the new standard of care. South Africa is good at collecting data on new interventions and using those data to inform policy and how interventions are rolled out on a broader scale.”

McKenna says BPaL is attractive, with three drugs and only six months of treatment.

However, “it was studied in a small group of 109 patients in the Nix-TB trial, which is less than what’s usually expected by regulatory authorities tasked with evaluating the efficacy and safety of new medicines. Phase 3 trials are typically much larger and include an internal concurrent control arm. Because the Nix-TB trial was a single-arm study, it is difficult to say how it compares with other regimens.

“Randomised control trials (RCTs) are the gold standard and should remain the expectation in TB. RCTs are important for informing us about the efficacy of a new treatment, for example, its ability to cure TB and prevent relapse, and about whether it is safe and tolerable compared with the existing standard of care. Large, randomised trials allow us to compare new regimens to what is already out there, while minimising bias.”

There are no RCT data on how the BPaL regimen compares with other cutting-edge regimens used to treat highly resistant forms of TB as yet.

Professor Keertan Dheda, a general physician, pulmonologist and critical care specialist who heads the division of pulmonology at Groote Schuur Hospital and the University of Cape Town, says the BPaL regimen is definitely a milestone worth celebrating.

“We all hope that patients who receive BPaL will be better off and have improved outcomes.”

Asked about why the BPaL regimen could not be used as a single regimen for all TB patients, Dheda explains that the standard six-month TB regimens are low-cost and still offer good outcomes for people who do not have drug-resistant TB.

“While using one regimen like the BPaL regimen for everyone [both drug-sensitive and drug-resistant TB] with TB in large numbers will have obvious short-term benefits, in the long run there would be more rapid development of resistance [including the spread of resistant strains in the country] and more drug-related toxicity.”

The bigger picture

Dheda says the overall incidence of TB in South Africa has been gradually declining over the past 10 years but remains substantial, with almost 400 000 people becoming newly ill from TB each year.

“South Africa remains one of those countries with the highest incidence of TB globally,” says Dheda. “However, the situation has improved considerably, with the department of health having done a good job of introducing a number of interventions that have made a difference.

“Some of the key interventions include improving the diagnosis and treatment of HIV (a major risk factor for TB); the introduction of state-of-the-art molecular diagnostic tests throughout the country; the introduction of newer drugs to treat drug-resistant TB, such as bedaquiline and delamanid; and the use of TB preventive therapy in high-risk groups.”

While finding better treatments is clearly important, Dheda says there are many interventions that could cause a substantial reduction in TB cases and deaths.

“In the longer term, good governance and economic prosperity will have the biggest impact on TB. It is a disease associated with poverty and overcrowding, and the TB burden automatically decreases with better living standards independent of the use of better diagnostics and drugs.

“Another potent driver of TB in South Africa is HIV. Thus, efforts to improve the diagnosis of HIV and initiating antiretroviral treatment have and will continue to have a major impact on reducing TB numbers.

“Poor lung health associated with smoking and biomass fuel exposure [the burning of fossil fuels in homes for cooking and eating, without proper ventilation] is also a major driver of TB, and efforts to curb this will have an impact.”

Read | Reimagining health in the Eastern Cape: Healthcare workers are key

Dheda comments on another critical intervention: “We need to move to an active case finding strategy, whereby diagnosis and case-finding are moved out of clinics and hospitals, and into the community. It is only in this way that we can have a major impact on interrupting the TB transmission cycle.

“We are engaged in innovative studies to implement a scalable community-based active finding strategy, using portable molecular tools. However, other models, such as using screening apps, will probably also be effective,” he says.

This article was produced by Spotlight – health journalism in the public interest

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners