Alternative name: Rubeola

The main features of measles are flu-like symptoms – a high fever, runny nose, hacking cough and conjunctivitis (red eyes,) leading up to the appearance of a typical skin rash that usually covers the entire body.

The measles virus is spread via droplets from the nose and throat of people infected with measles. Complications, which include middle-ear infection, croup, pneumonia, diarrhoea and encephalitis (inflammation of the brain), can be severe and in rare cases even fatal.

Measles was first described by Rhazes, a Persian physician in the 10th century. A Scottish physician, Francis Home, demonstrated that measles was caused by an infectious agent in 1757. In 1954, the virus that causes measles was identified in Boston, USA by John Enders and Thomas Peebles.

The history of measles underwent a complete change with the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1963. Even today, despite the availability of a vaccine, measles remains one of the leading causes of death in young children all over the world.

Measles is a human disease and doesn’t occur in animals.

Who gets measles?

In 2016 there were 89,780 measles deaths globally, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). This became the first year in which measles deaths dropped below 100,000 per year.

The prevalence of measles (rubeola) in South Africa has also decreased in the last decade thanks to concerted efforts to vaccinate all children. Excellent vaccination rates have been achieved in some provinces, notably the Western Cape and Gauteng. However, others still lag behind, particularly the Eastern Cape and many rural areas.

In some developing countries that don’t have measles vaccination programmes, measles is still common in children under the age of two. With this high and continual prevalence of the measles virus, children are likely to contract the virus early in life. However, with increased vaccination coverage, this pattern of exposure to the measles virus can be substantially reduced.

In developed countries, measles tends to be seen in adolescents or young adults as a consequence of waning immunity following incomplete vaccination. Measles control and virtual elimination can, however, be achieved with sufficient commitment and expenditure in any country.

It’s important to note that measles is a very serious disease. Before the measles vaccine became widely available, 2.6 million deaths resulted from measles infection internationally in 1980 alone. How fortunate it is that this life-saving vaccination is now available. Measles vaccination resulted in an 84% drop in measles deaths between 2000 and 2016.

Symptoms of measles

The earliest symptoms of measles are:

- High fever, rising over three days to 39°C or 40°C

- Runny nose

- A harsh, dry cough

- Red, inflamed eyes (conjunctivitis) and aversion to bright light

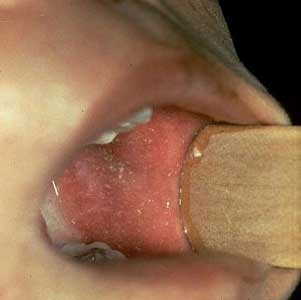

Once these symptoms start, small white spots with a red base can be seen on careful examination of the inside of the mouth, usually opposite the molar teeth on the inside of the cheeks. These are known as Koplik’s spots (see picture below).

These spots are unique to measles and can help an experienced health professional to confirm the diagnosis. However, the spots can easily be missed since they appear and disappear in the space of less than a day.

The symptoms listed above rapidly become increasingly severe and are at their worst once the rash appears.

The rash of measles usually appears 3-5 days after the symptoms start. A red or reddish-brown rash that’s slightly raised to the touch usually first appears on the forehead. The rash spreads to the rest of the face and, typically, appears behind the ears and neck. Within 24 hours the entire face, upper arms and chest become involved.

Over the next 24 hours, the rash spreads over the back, stomach and thighs, eventually reaching the feet by the third day. As the rash progresses, the individual spots typically tend to merge into one another (see picture below).

Once the rash reaches the feet, there’s usually a rather sudden improvement, including a drop in temperature. If the temperature doesn’t fall at this time, a complication should be suspected. The rash will start to fade and turn brownish, followed by some peeling.

It’s useful to note that, although the process isn’t visible, the rash is occurring internally as well, involving the respiratory tract and the gut.

This explains the typical measles hacking cough, the common complications of croup and measles pneumonia, and also the diarrhoea that may occur.

What causes measles?

Measles is caused by the measles virus (a virus in the paramyxovirus family), which occurs in humans everywhere in the world, except where almost 100% of the population has been vaccinated.

Measles (rubeola) is highly contagious and almost everyone coming into contact with an infectious person will contract the disease, unless they have had measles before or have been vaccinated.

If a person who hasn’t been vaccinated comes into contact with someone who is infected with measles and breathes in droplets that contain the virus, they will rapidly become infected with the virus. Ninety percent of people who haven’t been vaccinated against measles will get the virus if they’re in contact with an infected person.

The spread of the disease from person to person is assisted by the fact that a runny nose with sneezing and coughing occurs in the early stages of the illness. A person is infectious from about 3 days before the rash appears and up to 5 days after its appearance.

What are the risk factors for measles?

As measles is highly contagious, anyone who hasn’t been vaccinated against it is at risk of the disease and its complications.

However, certain risks are greater for disadvantaged members of South African society, specifically those exposed to malnutrition, HIV prevalence and lack of adequate medical attention.

Overcrowding may also play a role by exposing children to high levels of the measles virus.

Measles is usually more severe in infants younger than one year, a group in which successful vaccination is difficult to achieve. Allowing measles to continue to circulate puts such children at risk. Keep in mind that measles vaccination isn’t simply a matter of protecting one’s own child, but protecting others as well.

Course and prognosis of measles

Although measles can be a serious illness, it usually follows a relatively short and predictable course.

Most children can be managed at home, possibly with some supervision from a healthcare professional.

How is measles diagnosed?

An experienced healthcare professional will usually diagnose measles on the basis of the typical rash.

But with the decreasing frequency of the disease, there are some doctors who see very few cases in their working lives. Mild measles is easily confused with rubella (German measles) and other viral illnesses causing a rash.

Measles is a notifiable disease. This means that the South African Department of Health requires that all suspected cases of measles be investigated and that laboratory tests be done at state expense. This requires a blood sample to check for the presence of measles antibodies and a urine sample from which the virus can be cultured.

In cases of pneumonia or other complications during a measles infection, samples such as sputum should be collected for the laboratory to identify any additional viruses or bacteria. This helps with the choice of the correct antibiotic.

Complications of measles

There are several serious complications that can occur in people with measles and complications are more likely to occur in malnourished children.

Vitamin A deficiency in particular worsens the course of the disease. This is because vitamin A is important for the protection of the skin and the mucous membranes of the eyes, respiratory tract and gut.

Measles also tends to be more severe in infants under one year and in any person who is immune-suppressed, for example due to HIV infection.

In impoverished areas of South Africa, measles used to take a high toll on children until vaccination campaigns greatly reduced the problem.

Measles-related complications include:

Croup

Croup occurs due to inflammation of the vocal cords and upper airways.

With croup, difficulty in breathing air into the lungs is accompanied by a high-pitched crowing sound. Urgent medical attention is necessary because of the danger of complete obstruction of the upper airways.

Pneumonia

Pneumonia may be due to infection of the lungs with the measles virus itself. More often pneumonia is the result of added infection in the damaged airways and lung surfaces by other viruses or bacteria.

Pneumonia becomes evident through rapid, difficult breathing, worsening cough and chest pain.

Middle-ear infection

Middle-ear infection is very common and is apparent from pain in the ear. This possibility should always be kept in mind in distressed infants, since they can’t communicate the site of pain.

Diarrhoea

Diarrhoea is usually mild, but in malnourished children it can be severe and prolonged, further compromising the child’s nutrition.

Conjunctivitis

Red, watery eyes result directly from the measles virus infection. This eye infection is known as conjunctivitis and is present in nearly all measles patients.

Secondary bacterial infection may also occur with measles. Bacterial infection can cause quite severe eye inflammation, which may possibly lead to scarring of the cornea with partial blindness. This is a particular risk in malnourished children, especially those who also have a vitamin A deficiency.

If a person has measles and there’s severe redness and tearing of the eyes, it’s important to see a doctor.

Tuberculosis

Measles is a serious infection and leaves the individual's immune system suppressed for some weeks to months afterwards. It’s believed that this often contributes to the flaring up or reappearance of tuberculosis in children in South Africa and other developing countries.

Herpes

An early consequence of the immune-system suppression that occurs with measles may be the development of painful mouth ulcers. These mouth ulcers are due to a herpes virus infection in the mouth. This fairly common complication is known as herpes stomatitis.

Encephalitis

Encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) occurs in about 1 in 1,000 cases of measles. The risk increases with the age of the child.

Because the encephalitis is believed to be an “allergic” type of reaction to the virus in the brain, there’s no correlation between the severity of the measles and the risk of encephalitis. Encephalitis can be a complication of even the mildest case of measles.

Encephalitis usually occurs 2-7 days after the start of the rash, when the child should be starting to recover. Symptoms are recurrence of fever, onset of headache, apathy, irritability and confusion. Some children may have seizures.

Most children recover from measles encephalitis within 2-3 days, but about one third remain comatose for days to weeks. Some children who develop measles encephalitis are left with mental retardation, deafness, paralysis or epilepsy, and a few may die.

A delayed, fatal form of encephalitis that appears weeks to months after measles can occur in immune-compromised children.

Sub-acute sclerosing pan-encephalitis (SSPE) is an extremely rare but dreaded condition, which usually occurs many years after measles infection. For unknown reasons, the virus persists in a weakened form in the brain of a very small number of people infected with measles. It eventually begins to cause degeneration in areas of the brain.

This complication usually first becomes evident with subtle changes in personality, sleep patterns and intellect (for example a fall-off in schoolwork). Other early changes are failing eyesight and repetitive jerky movements. Unfortunately, with SSPE, there’s a slow downhill progression to death in every case.

How is measles treated?

The majority of children with measles can be managed at home with simple remedies such as paracetamol to reduce fever.

Nutrition is very important, especially if the child was malnourished beforehand. It may be difficult to get children to eat because of vomiting, herpes mouth ulcers or lack of appetite. High-energy liquid foods and extra vitamins should be given. Additional fluids should be given by mouth when there’s diarrhoea.

A homemade rehydration solution for treating diarrhoea is as follows:

- ½ a teaspoon of salt

- 8 level teaspoons of sugar

- 1 litre of boiled, cooled water

Dissolve the salt and sugar in the water. Don’t be tempted to add extra salt or sugar, as this can be harmful.

In infants, breastfeeding should be maintained and encouraged, even if diarrhoea is present. More severe diarrhoea will require management in hospital.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that children younger than one year be given vitamin A supplements to reduce the risk of complications of measles. Consult your healthcare professional about the appropriate dose of vitamin A, which is taken by mouth.

Cleaning of the eyes with warm, salty water and cotton wool helps to prevent bacterial infection. Antibiotic ointment may be necessary if infection occurs.

The mouth should be cleaned with warm, slightly salty water. Herpes ulceration and additional bacterial infection may require an anti-viral drug and possibly an antibiotic.

In general, antibiotics should only be given if there are complications such as ear infection, pneumonia or definite bacterial-caused diarrhoea.

However, children at high risk of complications (e.g. those with severe malnutrition or HIV/AIDS) may be given broad-spectrum antibiotics at the outset to try to prevent the almost inevitable complication of bacterial infections.

Children with encephalitis require close nursing in hospital and a sedative drug if convulsions are a feature.

When to see a doctor

Any complications of measles will require a visit to the doctor or clinic for assessment and treatment.

Some complications such as severe croup, pneumonia, diarrhoea or encephalitis are emergencies that require admission to hospital.

How can measles be prevented?

When it becomes obvious from the typical rash that someone has measles, he or she has already been infectious for about three days.

However, contact with others should still be avoided for five days after the rash appears. School-aged children should remain out of school for this period.

It should be noted that someone exposed to measles may be incubating the virus and, if so, is regarded as being infectious for about nine days after exposure. This is important to know if you want to protect vulnerable persons, for example babies, immune-compromised persons and anyone with chronic illness.

In the event of exposure of a vulnerable person, measles can be prevented or modified to a variable extent by giving immunoglobulin (a protein capable of acting as an antibody) by intramuscular injection within five days. Immunoglobulin is prepared from adult serum that contains antibodies to measles,and provides "instant immunity".

Routine measles vaccination is given at 9 and 15 months in South Africa. The vaccination at 15 months is given as the combined measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine.

Vaccination of children younger than 9 months isn’t reliable because the mother’s antibodies that are still present in the child’s blood can neutralise the vaccine. On the other hand, these antibodies give some natural protection to children in the first months of life.

In recent years, universal vaccination days for measles and polio have been arranged by the Department of Health in South Africa. These are days when all children under 5 years should receive the vaccine, regardless of their previous vaccination record.

This is done in an effort to cover not only those children who haven’t received the vaccine for some reason, but also the small percentage of children in whom the vaccine doesn’t “take” or work.

In any event, a booster vaccine helps to give long-term immunity.

The measles vaccine is a live measles virus that has been specially weakened or attenuated by culturing techniques in the laboratory. After inoculation, the measles vaccine virus will infect a person and cause the proper, protective immune response without actually causing measles.

However, about 20% of infants develop a mild fever (37.5°C) and a slight rash, usually three to four days after vaccination. This mild fever usually lasts for about 24 hours, and then returns to normal.

Unfortunately, about one in a million children who has been given the vaccine will get an “allergic” type of encephalitis (compared to the 1/1,000 risk after natural measles infection). There’s also a one per million risk of sub-acute sclerosing pan-encephalitis (SSPE) – an extremely rare but dreaded condition which usually occurs many years after measles infection.

Measles vaccine is recommended for children with HIV infection because they’re at risk for severe measles. They tolerate the vaccine surprisingly well.

Reviewed by Prof Eugene Weinberg, Paediatrician at the University of Cape Town’s Allergy and Immunology Unit. April 2018.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners